Embarking on the Taoist path is like stepping into a world where every twist and turn carries profound meaning.

Taoism, an ancient philosophy deeply rooted in Chinese culture, offers a myriad of insights that resonate both in the annals of history and in the contemporary world.

This guide aims to simplify that vast expanse, touching upon its essential beliefs, the customs shaped by centuries of tradition, the core principles that govern its teachings, and so much more.

Table of Contents

Toggle

What is Taoism?

Just like Buddhism and Hinduism, Taoism is more akin to a way of life rather than a religion per se.

Taoism stands as one of China’s most profound and enduring philosophical/religious traditions.

Rooted deeply in ancient Chinese history, its teachings have evolved over millennia, yet its core remains centered around the enigmatic yet foundational concept of the “Tao”.

This term, although deceptively simple in its translation as “the Way”, encapsulates a vast spectrum of meanings, from the intrinsic nature of the universe, the eternal principles steering existence, to the indefinable force that pulsates behind all creation.

According to Taoism, the universe operates under an innate order, and that by recognizing and aligning with this natural flow, we can achieve a state of harmony and even enlightenment.

The essence of this philosophy is not about forcing your way through life, but rather being in sync with its innate rhythms.

Through Taoism, we can learn not just about the world outside but go deep into the mysteries of the inner self, finding a path of tranquility amidst life’s ceaseless ebb and flow.

Who is the Central Figure in Taoism?

Lao Tzu

Lao Tzu is revered as the traditional founder of Taoism. His very name evokes respect and translates to “Old Master.”

However, pinning down his historical existence proves challenging.

While some scholars argue he was a real person from the 6th century BCE, others suggest he might be a legendary amalgamation of various ancient thinkers.

Numerous legends have sprouted around Lao Tzu.

One enduring tale tells of his growing disenchantment with city life’s moral decline, pushing him towards a secluded mountain existence.

On his way, a gate guard named Yin Xi recognized Lao Tzu’s wisdom and pleaded with him to record his insights before embracing solitude.

Obliging, Lao Tzu is then said to have composed the “Tao Te Ching”, a core text in Taoism. For over two thousand years, this work has left its mark on Chinese culture, influencing not just philosophy but also arts, medicine, and martial practices.

Over time, Lao Tzu’s stature grew, leading not just to the spread of his philosophical teachings but also to his deification in religious Taoism and other East Asian traditions.

What are the Sacred Texts of Taoism?

Tao Te Ching

The Tao Te Ching comprises 81 concise chapters.

Written in a lyrical and elusive style, the text invites multiple interpretations. A recurring theme in the text is the celebration of simplicity, humility, and compassion.

The Tao Te Ching proposes that rulers embracing these traits can lead more effectively and that individuals imbibing them can find a deeper sense of satisfaction in life.

It occasionally adopts a counterintuitive approach, suggesting, paradoxically, that real strength may be found in perceived weakness and true power in humble demeanors.

The Tao Te Ching’s ripple effects are vast. Beyond Taoism, its wisdom has left an indelible mark on Chinese Buddhism, Confucianism, and even artistic pursuits like calligraphy.

Its universal themes and timeless advice have led to its translation into numerous languages across the globe, with countless commentaries aiming to decipher its profound wisdom with every interpretation adding a new dimension.

Daozang

The Daozang is known as the Taoist Canon and it signifies a comprehensive treasury of Taoist scriptures.

Spanning over 1,400 texts in approximately 5,000 volumes, the Daozang embodies the essence of Taoist liturgy, cosmology, and so much more.

The Daozang took shape primarily during the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. Each dynasty witnessed an effort to revise, expand, or curate the canon.

As a result, numerous editions of the Daozang have emerged over time, with the most well-known being the Ming-era version compiled in the 15th century.

These scriptures, divided into three broad categories, present a panorama of Taoist thought:

-

Daojia (Philosophical Taoism): This segment is devoted to foundational Taoist philosophy and contains works like the Tao Te Ching and Zhuang Zhi. They form the philosophical backbone of Taoism.

-

Daojiao (Religious Taoism): This section is larger and more diverse, spotlighting the liturgical, devotional, and ritualistic facets of Taoism. Within its confines are instructions for rituals, details about deities, guidance on morality, and scriptures related to Taoist cosmology.

-

Daozang Jiyao (Essentials from the Taoist Canon): A condensed version of the Daozang, it curates the essential texts, making Taoist teachings more accessible.

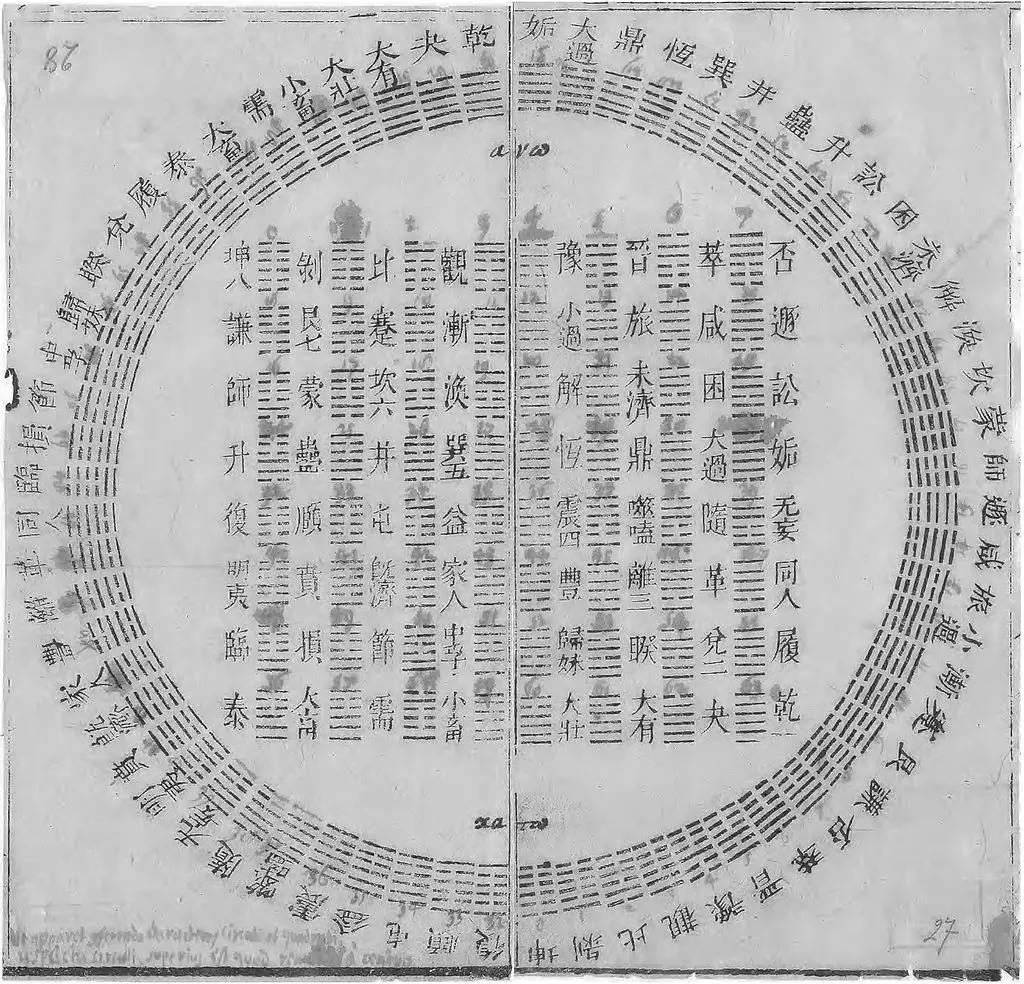

I Ching

The I Ching, often known as the “Book of Changes” in English, is one of the oldest of the Chinese classics.

With a history spanning over two and a half millennia, its initial chapters are believed to have been composed during the Western Zhou period (1000–750 BC) and then expanded over the following 1,000 years.

The I Ching is a guide to moral philosophy, decision-making, and understanding the universe. However, over time, it also acquired a reputation for being a divination tool.

The text’s primary framework is based on 64 hexagrams, each being a combination of six broken or unbroken lines. These lines can either be “yin” (represented by a broken line) or “yang” (depicted by an unbroken line).

Every hexagram is associated with a specific interpretation. The idea is that each hexagram provides insights into the nature of a particular phase in life.

The method of consulting the I Ching often involves casting a set of yarrow stalks, though in modern times, coin-tossing has become a more common method.

Based on the pattern, one derives a particular hexagram and then consults the text for wisdom regarding their situation.

The I Ching is also a profound repository of wisdom on life, ethics, and governance. Just like the Tao Te Ching, many of its passages are enigmatic, designed to stimulate deep contemplation rather than offer straightforward answers.

What are the Core Beliefs of Taoism?

The Tao

The Tao is understood as the fundamental, eternal principle that forms the source of all existence.

It remains beyond human comprehension, existing before any and everything.

This idea is beautifully encapsulated in the “Tao Te Ching,” which opens with the lines:

“The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao; The name that can be named is not the eternal name.”

When we speak of the Tao, we talk about something ineffable, a concept that transcends words and evades full articulation. Any endeavor to define it invariably falls short of encompassing its entirety.

It’s universal and omnipresent, a principle that courses through the entire universe, instilling life and movement into everything. The Tao is not just the originator of all things but also their ultimate destination.

Everything springs forth from the Tao and, in the end, returns to it.

For those who follow Taoism, the prime objective is to grasp and then align oneself with the Tao. Living in accordance with the Tao equates to embracing a life of simplicity, humility, and compassion, with a full acknowledgment of the interconnectedness of all entities.

In exploring the philosophical depths of different cultures, we often encounter ideas that, on the surface, seem worlds apart, but upon closer examination, share profound similarities.

Such is the case when comparing the Tao with Brahman from Hinduism or the concept of God in the Abrahamic traditions which you can read more about if you’re curious.

Yin and yang

Yin and Yang represent the duality inherent in all things, these concepts articulate the interplay between contrasting forces and how they contribute to the harmony of the universe.

Yin is typically characterized as passive, dark, cold, and possessing a downward directionality. Nature portrays Yin through symbols like the moon, water, and earth.

Within the broader societal constructs, it’s seen as feminine, tied to the night and carries introspective attributes.

On the other hand, Yang embodies activeness, brightness, warmth, and an upward movement. It finds its representations in the sun, fire, and sky.

Yang captures the essence of the masculine, the day, and the extrovert qualities of life. (Interestingly, in the Sri Yantra symbol, the downward pointing triangles symbolize Shakti or feminine energy, and the upward pointing triangles symbolize Shiva, the masculine.)

However, to regard Yin and Yang as strict opposites would be an oversimplification. They aren’t strictly opposing forces; rather, they’re complementary and deeply interconnected. Here’s my article on the Paradox of Yin and Yang if you’re interested in learning more.

The duality of Yin and Yang has practical applications across various aspects of Chinese culture, from medicine to martial arts, from dietary choices to Feng Shui, and even in the realm of human relationships and societal dynamics.

Te

Te, often translated as “virtue,” is the manifestation of Tao in all things and beings, and it embodies the inherent nature of them.

When considering Te in relation to human behavior, it represents the intrinsic strength that one can achieve when living in accordance with the Tao.

Te is about authentic and spontaneous behavior, arising from your true nature. It is not virtue in a moralistic sense, but rather the virtue of being in harmony with the Tao and allowing its flow to guide your actions.

When someone acts in congruence with their “Te,” they move effortlessly and effectively within the world.

Basically, when we are aligned with our genuine nature and by extension, the universe, our actions carry a distinct potency.

Like rediscovering an inherent power that emerges from being in harmony with the way things are. It’s the strength of a tree deeply rooted in the earth, standing firm against a storm, not through resistance, but by virtue of its true nature.

Immortality

Immortality, in a Taoist context, is less about eternal life in a physical form and more about aligning oneself with the Tao, and thus achieving a form of spiritual transcendence.

Taoist immortality is often portrayed through stories of legendary figures who achieved this state through various means.

Some of these means include alchemy, usually an elixir of life; such as the story of the Moon Goddess.

Historically, many Taoist sages went on quests in search of the elixir of life or secluded themselves in mountains to meditate and harness their Qi.

They believed that by purifying their bodies and spirits, they could achieve a state where their souls would transcend physical death, living on in higher realms or merging with the universal energy of the Tao.

Taoist immortality isn’t about defying death. It’s about recognizing death as a natural part of life’s cycle and seeking a deeper, spiritual form of existence that goes beyond the physical.

What are the Core Principles of Taoism?

Wu Wei

Wu Wei or “non-action” is often a misunderstood concept. It doesn’t really necessarily doing nothing, but rather it’s more akin to action that is in alignment with the natural order of things.

It’s about flowing with the current of life, rather than fighting against it.

In the Taoist philosophy, there exists the idea that the universe works in ways that are spontaneous, and that humans, as part of this universe, can benefit by aligning with this natural spontaneity.

This is where Wu Wei comes into play. It represents the art of effortless action.

To understand Wu Wei, imagine a tree growing. It doesn’t try to grow; it just grows.

Or consider water flowing down a hill. It doesn’t force its way; it just flows, taking the path of least resistance.

Practicing Wu Wei means taking actions that are in alignment with our true nature and the greater nature of the world. It means not being driven by personal desires or predefined doctrines, but rather responding to situations as they arise, in the most natural, uncomplicated way.

If you’re keen, you can learn more about how to implement the Art of Wu Wei in daily life.

Sanbao

Sanbao, which translates to “Three Treasures” are fundamental to understanding Taoism and its approach to health, longevity, and spiritual enlightenment.

The Sanbao consists of “Jing” (Essence), “Qi” (Vital Energy), and “Shen” (Spirit):

- Jing – often referred to as the body’s physical essence. It can be seen as a bio-energetic substance that’s foundational to life, closely linked with reproductive energy and our genetic makeup.

- Qi – the life force that permeates all living things. It flows through the body along specific channels called meridians. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, the flow of Qi in the human body plays a significant role in health and disease. A proper flow of Qi is associated with good health. In contrast, an imbalance can lead to disease. Qi is also a central concept even in the Japanese energy healing modality known as Reiki (wherein Qi equals Ki).

- Shen – represents consciousness. Shen is the divine, immortal part of our being, often depicted as the light around someone. It’s related to our mental faculties, emotions, and overall consciousness. Nurturing Shen is seen as the bridge to higher states of consciousness and union with the Tao.

In the journey of a Taoist, the process often begins with the purification and strengthening of Jing, which subsequently enhances Qi, leading to the illumination of Shen.

Ziran

Ziran encapsulates the idea of things being in their untouched, original state, acting according to their inherent nature without external interference. Which is why Ziran pretty much means “naturalness.”

Ziran is the embodiment of the Tao principle in all things, suggesting that every entity, from the largest star to the smallest grain of sand, follows its natural course.

It’s the universe’s way of being and doing without any pretense.

Embracing Ziran means a life where actions arise naturally from one’s inherent nature and circumstances.

For instance, consider an artist lost in the act of creation, where every brushstroke feels right, not because of some external standard but because it’s a genuine expression of their inner self.

This state of flow, where one’s actions are seamlessly aligned with their nature, is a manifestation of Ziran.

In many ways, Ziran is not just a principle but a way of life. It’s about recognizing the natural order of things and understanding that, often, the most genuine actions are those that arise without conscious effort.

Fan

Fan means “to return.”

The idea of “Fan” is built on the understanding that, in our lives, we often move away from our true nature, get entangled in complexities, desires, and societal constructs that take us farther from the simplicity and purity of our essential self.

These deviations, be they in the form of excessive desires, overthinking, or living against the natural rhythms, lead to suffering.

Taoist teachings advise a “return” to this inherent nature. This doesn’t mean regressing or going backward in a chronological sense, but rather rediscovering with the primal, unadulterated essence that exists within.

One of verses from the Tao Te Ching captures this concept beautifully:

“Returning is the motion of the Tao. Yielding is the way of the Tao. The ten thousand things are born of being. Being is born of not being.”

Who are the Deities of Taoism?

While some forms of Taoism focus more on philosophical aspects, other forms, especially religious Taoism, have a rich pantheon.

Here’s an overview of some of the most notable deities in Taoism:

- The Three Pure Ones (Sanqing): These are the highest gods in the Taoist pantheon and represent different manifestations of the Tao. (Similar to how the deities of Hinduism are considered as manifestations of Brahman.)

- Yuanshi Tianzun (The Celestial Worthy of the Primordial Beginning): Represents the beginning of all existence and the essence of life.

- Lingbao Tianzun (The Celestial Worthy of the Numinous Treasure): Embodies the laws of the universe.

- Daode Tianzun (The Celestial Worthy of the Way and its Virtue): Often identified with Lao Tzu.

- The Jade Emperor (Yuhuang Shangdi or Yudi): Regarded as one of the most powerful deities, the Jade Emperor oversees all of heaven and earth. He’s a significant figure in Chinese religious culture beyond just Taoism, including Confucianism and Chinese folk religion.

- The Eight Immortals (Ba Xian): A popular group of legendary figures, each of whom achieved immortality through the practice of Taoist teachings and principles. They are often depicted in art and literature and are known for their adventures, each having a unique power. The Eight Immortals are He Xiangu, Cao Guojiu, Li Tieguai, Lan Caihe, Lu Dongbin, Han Xiangzi, Zhang Guolao, and Zhongli Quan.

- Guan Yu: While primarily known as a historical figure from the Three Kingdoms period and a deity in Chinese Buddhism and Confucianism, Guan Yu is also venerated in Taoism as a god of war, righteousness, and loyalty.

- Mazu: The goddess of the sea, particularly revered in coastal areas and among fishermen. She is believed to protect seafarers and is widely venerated in southeastern China, Taiwan, and other parts of East Asia. I was even able to see temples dedicated to her in Malaysia and Singapore.

What are the Practices of Taoism?

- Meditation: Meditation allows you to quiet the mind and dive deep into your inner self.

- Tai Chi and Qigong: Tai Chi and Qi Gong are physical practices that combine movement, breathing, and meditation. They’re designed to cultivate and balance Qi.

- Feng Shui: Feng Shui is the ancient Chinese art of placement and design that seeks to harmonize one with their surroundings.

- Traditional Chinese Medicine: Rooted deeply in Taoist principles, it employs methods like acupuncture, herbal remedies, and diet to balance the yin and yang energies in the body.

- Alchemy: Taoist alchemy has both an external and internal aspect. While the external involves the quest for an elixir to ensure immortality, the internal focuses on spiritual purification and transformation.

Taoism by Country

-

China: The cradle of Taoism, China has revered the Taoist tradition for millennia. Temples such as the White Cloud Temple in Beijing and monasteries like the Wudang Mountains are pivotal centers of Taoist learning and practice.

-

Taiwan: Taoism is a major religious force here. Temples dot the island, and events like the Qingshan King Ritual and the Mazu pilgrimage draw large crowds. Taoist deities are revered, and festivals in their honor are elaborate and widespread.

-

Hong Kong: Temples dedicated to Taoist worship, such as Wong Tai Sin Temple, are major religious sites in Hong Kong. What makes Wong Tai Sin Temple even more unique is that it is a religious syncretic temple that houses Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian deities all in one site.

Vietnam: The Quan Thanh Temple is among the most significant Taoist temples in Hanoi. Dedicated to Tran Vu, a Taoist deity representing the North and known for his role in combating evil spirits. The temple’s history dates back to the 11th century during the Ly Dynasty, making it one of the Four Sacred Temples built to honor the four protectors of the four directions.

Korea: Introduced during the Three Kingdoms period, Taoism melded with Buddhism and Confucianism. Notable sites include the Dragon Spring Hermitage in South Gyeongsang.

Singapore: Being a multi-cultural country, Taoist temples such as the Thian Hock Keng are classic landmarks amongst others. It’s a temple dedicated to the aforementioned Mazu.

Malaysia: The Thean Hou Temple in Kuala Lumpur, yet another temple dedicated to Mazu, is not only one of the most resplendent temples in the area, but is yet another prominent Taoist landmark in the country.

What are the Customs of Taoism?

- In many Taoist households and temples, altars are dedicated to ancestors as a form of veneration.

- Some Taoists might abstain from certain foods like garlic, onions, and other pungent vegetables. This is known as Jie, a form of fasting where one abstains from certain foods to clear the mind and body.

- Using methods like the I Ching, Taoists also practice the art of divination.

- There are several sacred mountains in Taoism that devotees make a pilgrimage to. Mt. Tai in Shandong, for example, is one such revered site.