Ancient Greece.

Beneath the gaze of the gods and the murmurs of muses, a form of storytelling arose that would captivate the world for millennia to come.

Whisper the term “Greek tragedy,” and you’re immediately enveloped by a tumultuous sea of forbidden love, heroic sacrifices, and fates so cruel they’d make even the bravest of mortals shudder.

But what, precisely, defines this mesmerizing art form?

Greek tragedy is like a mirror to humanity, reflecting our deepest desires, our most haunting fears, and the very essence of our mortal coil.

In ancient Greek culture, these plays were actually profound religious rituals! They served as both entertainment and enlightenment, guiding spectators through a cathartic journey of emotion, challenging them to question their place in the cosmos, and the whims of gods and fate.

In this article, we’ll delve into the Art of Greek Tragedies, taking a closer look at some of the classics and exploring the morals we can derive from them.

Table of Contents

Toggle

Origin of Greek Tragedies

In the annals of time, when Greece was still finding its voice in the world, the seeds of tragedy were sown, not in grand amphitheaters, but amidst the sacred groves dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine, ecstasy, and revelry.

Dionysian rituals were exuberant affairs. Worshipers, fueled by the intoxicating essence of wine, would lose themselves in ecstatic dances and songs, giving themselves over to the divine spirit of the god they revered. These choral performances, known as “dithyrambs,” were primal in their energy.

Composed in honor of Dionysus, they narrated myths, celebrating his life and adventures.

But, as with all things, change was inevitable. Over time, the simple choral narratives began to evolve.

A single actor, known as the “hypokrites,” would step away from the chorus to assume the role of a character, responding to the chorus and thereby introducing a semblance of dialogue. With this innovation, the narrative landscape of these performances expanded, giving birth to a richer, more complex form of storytelling.

The foundation for the grand Greek tragedies, as we recognize them today, was laid. The stage was set, quite literally, for tales that would echo through the ages, resonating with generations far removed from those ancient Dionysian revels.

3 Major Greek Tragedians

In the world of Greek tragedy, three names shine brighter than the rest:

- Aeschylus: Hailed as the “Father of Tragedy“, Aeschylus was the pioneer who transformed the early dithyrambs into dramatic masterpieces. He expanded the number of actors, allowing for richer interaction and more complex plotlines.

- Sophocles: Following in Aeschylus’ footsteps, Sophocles emerged as the “Innovator,” adding yet another actor to the stage and further diminishing the role of the chorus. This allowed for more intricate character dynamics and deeper explorations of personal conflict.

- Euripides: Often perceived as the “Modernist” among the three, Euripides was known for his nuanced portrayal of characters, especially women, and his tendency to question traditional religious and societal norms. His tragedies often blurred the lines between protagonist and antagonist, presenting characters with profound psychological depth and moral ambiguity. Euripides’ works were, at times, controversial, but they showcased a reality that was far more in tune with the human experience.

5 Elements of a Greek Tragedy

The carefully crafted structure of Greek tragedy is as follows:

Prologue: Before the drama unfolds, the prologue sets the stage, providing context and piquing curiosity.

Parodos: With the grandeur of song and dance, the Chorus makes its presence known, seamlessly guiding the audience into the heart of the play.

Episodes: These are the core acts or scenes, the backbone of the tragedy. Here, characters grapple with their fates, decisions, and the play’s central conflicts.

Stasimon: Between episodes, the Chorus offers its reflections. Through choral odes, it delves deep into the play’s themes, often evoking emotion and contemplation.

Exodus: As the story reaches its zenith, the climax and the denouement unveil, leaving behind profound moral lessons and an audience in awe.

7 Greek Tragedy Characters

1. Oedipus

Oedipus, the protagonist of Sophocles’ tragic play “Oedipus Rex,” is a character plagued by fate and destiny. Born to King Laius and Queen Jocasta of Thebes, the Oracle of Delphi foretells that he will murder his father and marry his mother. In an attempt to prevent this prophecy from coming true, Laius orders his son to be left on a mountain to die.

However, Oedipus is rescued and raised by the king and queen of Corinth. Unaware of his true lineage, Oedipus later encounters Laius on a journey and kills him in a dispute. He then solves the riddle of the Sphinx, freeing Thebes from her curse and subsequently marrying the widowed queen, his biological mother, Jocasta. The tragic revelation of his actions and the truth of his birth leads to Jocasta’s suicide and Oedipus blinding himself.

Themes:

-

Fate vs. Free Will: The most predominant theme of Oedipus Rex is the inexorability of fate. Despite the attempts of Oedipus and his parents to change destiny, they still fall into its trap, raising questions about the nature of fate versus free will. Is it possible to escape one’s destined path, or are some events truly inevitable?

-

The Quest for Truth: Oedipus is unwavering in his pursuit of the truth, believing that revealing the murderer of King Laius will save Thebes from a plague. However, his determination to uncover the truth brings forth his own ruin, suggesting that there are some truths that might be too harrowing to bear.

-

Sight vs. Blindness: Throughout the play, the idea of sight is juxtaposed with blindness. While Oedipus is physically able to see, he is “blind” to his own reality. It’s only when he understands his true identity that he blinds himself, showing that insight doesn’t always require physical sight.

-

Punishment: Oedipus’s self-inflicted blinding is symbolic of the inner torment he feels. It raises questions about the nature of crime and punishment. Was Oedipus’s punishment just, given that his actions were predicted by fate?

2. Prometheus

Prometheus, whose name means “forethought,” is a Titan known for his intelligence and as a champion of humankind. Despite being on the side of the Titans during the Titanomachy, Prometheus sought to help humans, often putting him at odds with the Olympian gods, especially Zeus.

The most famous tale of Prometheus is his theft of fire. Seeing that humans were living in darkness and cold, he decided to steal fire from the gods and bring it to them. For this, Zeus punished him severely. He was chained to a rock in the Caucasus Mountains where every day an eagle would eat his liver. Each night, his liver would regenerate, only to be consumed again the next day. This eternal torment was set for Prometheus as a consequence of his rebellious act.

However, his torment didn’t last forever. He was eventually freed by the hero Heracles (Hercules in Roman mythology.)

Themes:

Sacrifice for the Greater Good: Prometheus endured suffering for the sake of humanity. He saw the potential and hope in humans and believed that the gift of fire – symbolizing knowledge and enlightenment – was worth any personal cost.

Actions have Consequences: While Prometheus’s intentions were noble, he overstepped the boundaries set by the gods. His story warns of the severe consequences that can arise when one challenges the established order or seeks to play god.

Hope: Despite his daily torment, Prometheus never lost hope. His resilience shows that enduring suffering can eventually lead to redemption, as evidenced by his eventual freedom at the hands of Heracles

3. Ajax

Ajax, also known as Ajax the Great, was a hero of the Trojan War and a warrior of immense strength and valor. He was the son of Telamon, the king of Salamis, and was described as being second only to Achilles in terms of his prowess on the battlefield. While he played a crucial role in many battles and events during the war, his story took a tragic turn in its aftermath.

After the death of Achilles, a dispute arose over who should inherit his magnificent armor, forged by the god Hephaestus. The contenders were Ajax and Odysseus. When the armor was awarded to Odysseus through the judgment of the Greek leaders, Ajax was consumed by grief and rage. Feeling disrespected and dishonored, he planned to kill the Greek leaders in retaliation. However, the goddess Athena intervened, making him delusional. In his confused state, Ajax slaughtered livestock, believing they were his enemies.

Upon realizing what he had done when his sanity returned, Ajax was filled with shame and despair. Unable to bear the humiliation, he chose to end his own life using the sword given to him by Hector, a Trojan prince.

Themes:

Honor and Pride: In Ajax’s tragedy lies his deep-seated sense of honor. The loss of Achilles’ armor wasn’t really about the armor itself but the recognition it represented. Ajax’s pride couldn’t reconcile with the perceived slight.

The Consequences of Wrath: Ajax’s uncontrollable anger, exacerbated by Athena’s intervention, led him down a path of self-destruction. His story serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of letting emotions, especially anger, govern one’s actions.

The Fragility of the Human Psyche: Despite his immense physical strength, Ajax’s mental and emotional state was fragile. The dissonance between his self-image and external validation resulted in a tragic breakdown.

4. Medea

Medea is a figure of great sorcery and power, a princess of the barbarian kingdom of Colchis. She’s most famously known from Euripides’ play, “Medea”, which chronicles the events after the tale of Jason and the Argonauts. Medea falls deeply in love with Jason, betraying her own family and killing her brother to aid him in his quest for the Golden Fleece.

The two flee to Corinth where they establish a family and live for ten years. However, for the sake of political advantage, Jason decides to marry Glauce, the daughter of King Creon of Corinth. Medea, overcome with betrayal, is banished by Creon but given a day’s reprieve. In this time, she enacts a horrific vengeance. She sends Glauce a poisoned dress, killing her. King Creon dies as well trying to save his daughter. The tragedy reaches its peak when Medea, in a bid to hurt Jason the most, kills their two children.

She then escapes to Athens on a chariot provided by the god Helios, leaving a devastated Jason behind. The play ends with Medea achieving her vengeance, and Jason is left cursing his decisions.

Themes:

Love and Betrayal: Medea’s intense love for Jason, which led her to commit unspeakable acts for his sake, is countered by Jason’s betrayal. Their story shows the destructive potential of love when it turns into obsession and resentment.

Justice and Vengeance: Medea sees her actions, as terrible as they are, as a form of justice for Jason’s betrayal. The line between justice and revenge is blurred, with Medea exacting a punishment far exceeding the crime. Or does it?

Feminine Power: Medea, in a world dominated by men, uses her intelligence, her knowledge of potions, and her barbarian status to defy the expectations of her role. She becomes the agent of her own fate.

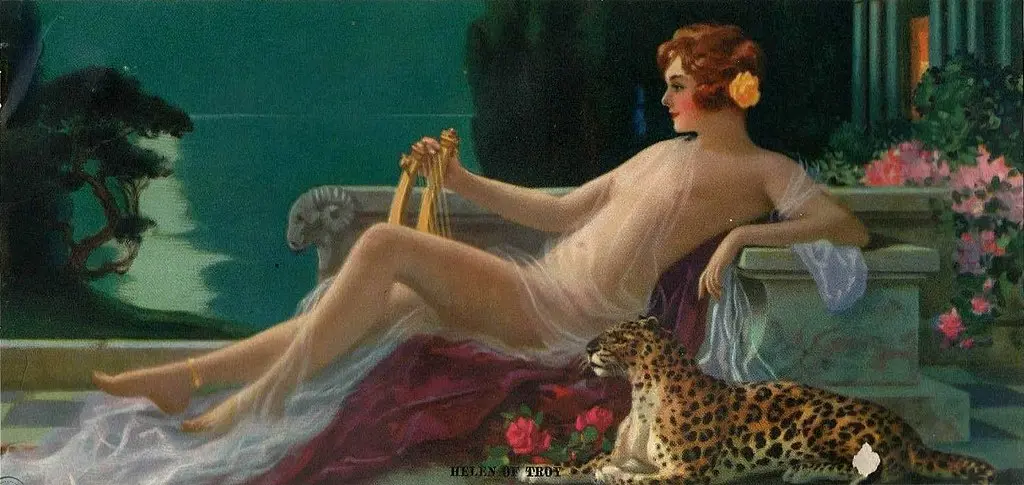

5. Helen

Euripides’ “Helen” is a radical reimagining of the infamous legend of Helen of Troy. In this tale, Helen never went to Troy at all. Instead, the gods crafted a phantom Helen, an ethereal double, which Paris took to Troy. The real Helen, meanwhile, was carried off to Egypt by Hermes on Zeus’s orders, where she waited for the day she would be reunited with her husband, Menelaus.

The play commences seventeen years after the beginning of the Trojan War. Helen has been in Egypt all this time, mourning her forced separation from Menelaus and enduring the advances of the local rulers. She’s tarnished by the reputation of her phantom’s actions in Troy and is reviled as the face that launched a thousand ships. Yet, she remains chaste, holding onto hope that Menelaus might one day find her.

As fate would have it, Menelaus eventually lands in Egypt after being shipwrecked, but he’s in hiding, fearing the Egyptians would kill him if they found him. Neither is aware of the other’s presence until they’re unexpectedly reunited.

The reunion is touching, but their troubles aren’t over. The current ruler, Theoclymenus, intends to marry Helen and won’t easily let her go. With wit, guile, and a little divine intervention, Helen and Menelaus plot their escape. Their journey home is fraught with peril, but their love and determination see them through.

Themes:

-

Illusion vs. Reality: Euripides challenges the traditional narrative, suggesting that sometimes wars are fought over illusions. This can be seen as a critique of society’s propensity to be swayed by misconceptions, leading to dire consequences.

-

Feminine Virtue: In this narrative, Helen is not a passive beauty but a woman of action, trying to maintain her honor in a foreign land, just like Sita from the Ramayana. The story challenges the traditional blame laid upon her and reframes her as a victim of circumstances and divine whims.

-

Reputation: Helen’s image is tainted by events beyond her control, reflecting on how society often creates reputations based on misinformation.

6. Heracles

The Heracles of Euripedes delves deep into the life of the famed Greek hero after he’s completed his Twelve Labors. In this tragedy, while Heracles is away in the Underworld, a usurper named Lycus takes over Thebes, planning to kill Heracles’ wife, Megara, and their children to ensure his rule remains uncontested.

Megara and her children are given some respite, waiting for Heracles’ return, but they’re under no illusions about their grim fate if he doesn’t return soon. As they are about to be executed, Heracles arrives just in time to save his family. He kills Lycus and liberates Thebes.

However, the respite is short-lived. Hera, who has always detested Heracles, sends Madness upon him. In his insanity, Heracles believes his own children are those of his mortal enemy, Eurystheus, and ends up killing them along with Megara.

When he finally regains his sanity and realizes the horror of his actions, he’s devastated. Theseus, his old friend, arrives and tries to console the grieving hero. It is Theseus who persuades Heracles not to take his own life but to find a way to atone and live on.

Themes:

Fate: As with many Greek tragedies, Heracles’ story raises questions about fate’s role in human suffering. Can humans truly be blamed for actions preordained by the gods?

The Fragility of Sanity: Hera’s intervention shows how a person’s mental state can be fragile. Heracles, the strongest of all men, becomes the weakest when his sanity is robbed.

Strength in Companionship: The arrival and consolation of Theseus shows the value of true friendship during times of despair. Even in our darkest hours, there’s hope through connection and understanding.

7. Orpheus

One of my favorite tales in Greek mythology, Orpheus is best known for his unmatched musical talents and his tragic love for Eurydice. Orpheus, the son of the muse Calliope, could charm all living things and even stones with his music.

The tale takes a tragic turn when Eurydice, shortly after their marriage, is bitten by a snake and dies. Unable to accept her death, Orpheus travels to the Underworld to retrieve her. With the power of his lyre and enchanting voice, he manages to soften the hearts of Hades and Persephone, the rulers of the Underworld. They agree to release Eurydice on one condition: Orpheus must not look back at her until they’ve both reached the mortal realm.

However, just as they approach the exit, Orpheus, in a moment of human doubt, turns to see if Eurydice is following him. She is immediately pulled back into the Underworld, this time forever.

Devastated, Orpheus roams the earth, avoiding all human contact. He meets a tragic end at the hands of the Maenads, who, in a frenzied state, tear him apart. His lyre is then placed amongst the stars, and his soul returns to the Underworld, reuniting with Eurydice.

Themes:

Power of Love: Orpheus’s journey into the Underworld epitomizes the lengths one might go for love. It showcases love’s capacity to challenge even the barriers of life and death.

Human Doubt: Despite being a demigod with immense talents, Orpheus’s single act of doubt proves to be his undoing. This element of the tale points out the inherently flawed nature of humans.

Nature of Death: The tale is also a reflection on the permanence of death and the human desire to overcome it. It suggests that while love can challenge the boundaries of death, ultimately, it cannot conquer it.

The Art of Tragedy

Greek tragedy is an exploration into the depth of human emotions, morality, and the duality of our existence. But what really makes a tragedy, a tragedy? They would usually involve:

Catharsis: This represents the emotional release experienced by the audience after witnessing the tragic events of the play. Through feelings of pity and fear, the audience undergoes a purification, a cleansing of the soul, making sense of their own emotions and the world around them.

Hamartia: This tragic flaw, often stemming from the protagonist’s character or a mistake they make, inevitably leads to their downfall. It’s a potent reminder of the imperfections inherent in humanity, highlighting the delicate balance between our strengths and vulnerabilities.

Hubris: The age-old warning against excessive pride, especially towards the gods. Many tragic figures meet their end due to this overconfidence, a stark reminder of the importance of humility and understanding one’s place in the grand scheme of things.

Anagnorisis: The moment of realization, when a character discovers a truth about themselves or their situation. It’s the turning point, where the narrative shifts, and the tragic inevitability becomes more pronounced.

Peripeteia: Life is unpredictable, and Greek tragedies encapsulate this through sudden reversals of fortune. Just when a character seems to have everything in control, fate intervenes, leading to unexpected outcomes.