The Mahabharata, an ancient Sanskrit epic along with the Ramayana, stands as a monumental literary work, unparalleled in its depth and complexity.

Revered for thousands of years, it transcends storytelling to embody the cultural essence of ancient India. This grand epic, attributed to the sage Vyasa, is not just a tale of heroes and villains, but a profound exploration of the human condition, dharma (duty), and the intricate web of life’s moral challenges.

Comprising over 100,000 shlokas or couplets, the Mahabharata is the longest epic poem in the world!

Its narratives have influenced countless generations, weaving themselves into the daily life and spirituality of millions.

In this article, we’re going right into the heart of the Mahabharata, unraveling its full story, examining the life lessons and themes it presents, and exploring its enduring influence in other cultures.

Table of Contents

Toggle

The Mahabharata in Various Cultures

- Indonesia: In Java and Bali, the Mahabharata is integral to the traditional shadow puppet theatre (Wayang Kulit) and masked dance-drama (Wayang Wong). These performances not only tell the stories of the Mahabharata but also incorporate local values, creating a unique blend of Hindu and Indonesian cultures.

- Cambodia: The Mahabharata’s influence in Cambodia, particularly in Siem Reap, is most visible in the bas-reliefs of ancient temples like Angkor Wat. These carvings depict various scenes from the epic, showcasing its significance in the Khmer Empire. The traditional Apsara dance often includes narratives from the Mahabharata.

- Malaysia: Similar to Indonesia, Malaysia has a tradition of shadow puppet theatre, especially in the state of Kelantan. The Wayang Kulit performances in Malaysia often include stories from the Mahabharata, adapted to include local Malay cultural elements.

What is the Story of the Mahabharata?

To give justice to the Mahabharata, we will be going in-depth to get a more thorough understanding of the entire narrative. The beginning tends to have a lot of character introductions and it might be hard to keep up but it does get easier as the central story unfolds and the main characters take the stage.

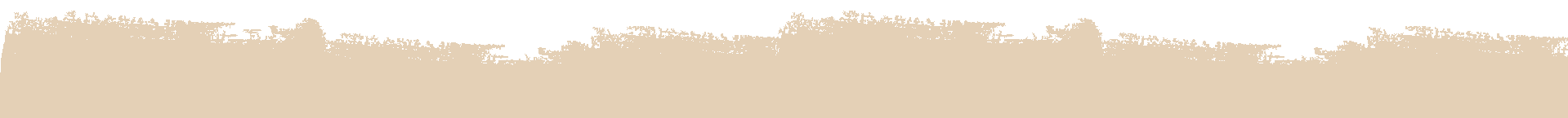

The story goes that Vyasa, with the monumental task of composing the Mahabharata, sought a scribe capable of comprehending and writing down his complex and divinely inspired verses without pause. He requested Lord Ganesha, the deity known for his wisdom, to assist him in this endeavor.

Ganesha agreed to be the scribe for the Mahabharata on one condition – Vyasa had to recite the epic continuously without pause. In response, Vyasa set a counter-condition that Ganesha must understand each verse before he wrote it down. This condition led to a unique process of composition, where Vyasa composed the epic in a way that occasionally contained complex verses that would make Ganesha pause and think, giving Vyasa time to compose further.

Legend also has it that Ganesha, writing the epic, broke one of his tusks to use as a pen when the quill initially provided wore out, demonstrating his dedication to the task.

Shantanu and Ganga

The ancestral narrative of the Mahabharata begins with the story of King Shantanu of Hastinapur. Shantanu, a noble and just king, encounters a celestial beauty on the banks of the Ganges river. She is Ganga, the personification of the holy river. Struck by her divine charm, Shantanu proposes marriage. Ganga agrees but with a condition: Shantanu must never question her actions. If he does, she would leave him.

Their marriage brings forth seven sons, each of whom Ganga drowns in the river soon after birth. Shantanu is tormented by her actions but remembers her condition. It is only when she is about to drown their eighth son that Shantanu protests, unable to bear it any longer. Ganga then reveals her reasons: the children were celestial beings cursed to be born as humans and she released them from their human form. With Shantanu having broken his vow, Ganga leaves him, taking their surviving son with her, promising to return him once he is grown.

Bhishma

The child Ganga took away is named Devavrata, who grows into an exemplary prince, skilled in warfare and knowledgeable in statecraft. Ganga returns him to Shantanu, who is overjoyed to reunite with his son.

Later, Shantanu falls in love with Satyavati, a fisherwoman, but her father refuses the marriage, concerned about the throne’s succession and Satyavati’s children’s future. Satyavati is known for her distinct scent and her lineage from a cursed apsara (celestial nymph).

Devavrata, learning of his father’s dilemma, vows never to ascend the throne and to walk the path of brahmacharya (celibacy) throughout his life, ensuring that the throne would be available for Satyavati’s progeny. Impressed by this immense sacrifice, the gods grant him a boon of Ichcha Mrityu (choosing the time of his own death), and he comes to be known as Bhishma, one of the greatest warriors and statesmen in the epic.

After marrying Shantanu, she bears him two sons, Chitrangada and Vichitravirya. Chitrangada, the elder, dies in a battle, and Vichitravirya becomes king.

The Birth of the Kuru Lineage

After the death of King Shantanu, his youngest son Vichitravirya ascended the throne of Hastinapur. Bhishma, adhering to his vow of celibacy and commitment to the throne, undertook the responsibility of finding brides for Vichitravirya. He attended the swayamvara of the three princesses of Kashi – Amba, Ambika, and Ambalika. In a bold move, Bhishma won the contest and abducted all three princesses to be the wives of Vichitravirya.

However, Amba, the eldest princess, revealed that she was already in love with Salva, the king of Saubala, and wanted to marry him. Respecting her wishes, Bhishma sent her back to Salva. But Salva, humiliated by the circumstances of her abduction, refused to accept her. Amba, finding herself rejected and humiliated, held Bhishma responsible for her plight and vowed to seek revenge. She undertook severe penances and eventually received a boon that would enable her to be the cause of Bhishma’s death in her next life.

Vichitravirya, however, dies young without producing an heir, leaving the Kuru dynasty in a precarious situation. The continuation of the lineage becomes a matter of great concern. Satyavati, then, calls upon her first son, Vyasa, a sage of great repute, born before her marriage to Shantanu, to father children on the widows of Vichitravirya as per the practice of Niyoga, an ancient custom where a kinsman could father children on behalf of a deceased male relative.

Vyasa agrees to Satyavati’s request and approaches Ambika and Ambalika to father heirs for the Kuru dynasty. Ambika, upon meeting the austere and grim Vyasa, closes her eyes in fear, and as a result, her son, Dhritarashtra, is born blind.

Ambalika turns pale upon seeing Vyasa, and thus her son, Pandu, is born anemic. Alarmed by the prospects of a blind and a weak king, Satyavati asks Ambika to go to Vyasa again. However, Ambika, scared, sends her maid instead. The maid, unafraid and respectful, bears a healthy and wise son named Vidura.

Pandu, Kunti, and Madri

The narrative of the Pandavas begins with their father, Pandu, who was king of Hastinapur. Pandu, however, is not destined to enjoy a long reign. While on a hunting expedition, he mistakenly kills a sage named Kindama, who, along with his wife, had transformed themselves into deer and were in coitus. With his dying breath, the sage curses Pandu, proclaiming that he will die the moment he seeks to be intimate with a woman. Shocked and distraught by the curse and the sin of killing a sage, Pandu decides to abdicate the throne and retire to the forest, along with his wives, Kunti and Madri.

In the forest, Kunti reveals a secret to Pandu. In her youth, she had received a boon from Sage Durvasa that allowed her to invoke any deity and bear a child by them. Seeing an opportunity to continue the lineage without defying the curse, Pandu encourages Kunti to use this boon. Consequently, Kunti gives birth to three sons: Yudhishthira from the deity Dharma, signifying righteousness; Bhima from the wind god Vayu, embodying strength; and Arjuna from Indra, the king of the gods, destined to be a peerless archer.

Madri, Pandu’s second wife, also uses the boon with Kunti’s help. She invokes the Ashwini Kumaras, the twin gods, and gives birth to Nakula and Sahadeva, known for their beauty and wisdom respectively.

Dhritarashtra, despite his blindness, becomes king of Hastinapur, as Pandu is considered unfit due to his health. Pandu, however, proves his prowess and rules the kingdom as a regent. Vidura becomes an important figure in the court, known for his wisdom and knowledge of statecraft.

The Young Kuru Princes

The story of the Kuru princes, the Kauravas and the Pandavas, begins with their early years, marked by contrasting upbringings and emerging rivalries.

The Kauravas, a hundred brothers led by Duryodhana, are the sons of Dhritarashtra while the Pandavas are the five sons of Pandu.

Raised together in Hastinapur, the princes display differing personalities and skills from a young age.

The Kauravas, particularly Duryodhana, grow envious of the Pandavas due to their prowess and popularity. This rivalry intensifies over time, setting the foundation for future conflicts. The Pandavas, known for their righteousness and skills, become favorites of the people and the court.

Kripacharya and Drona

Kripacharya, the royal teacher, initially trains both the Kauravas and Pandavas. He is known for his impartiality and wisdom. However, as the princes grow, the need for a more specialized teacher becomes evident.

Enter Guru Drona, a master of advanced military arts. Drona becomes the principal teacher of both sets of princes, instructing them in archery, warfare, and the use of divine weapons. Under Drona, Arjuna emerges as an exceptional archer, gaining the teacher’s special attention and favor.

Karna

Karna enters the story during the princes’ graduation ceremony, where they display their skills. He challenges Arjuna, seeking to establish himself as the superior archer. Karna, born to Kunti and Surya (the Sun God) before her marriage due to very same boon, is raised by a charioteer. Unaware of his true parentage, he grows up with a sense of bitterness and seeks recognition for his undeniable skills.

Duryodhana, recognizing Karna’s potential as an ally against the Pandavas, befriends him. He grants Karna the kingdom of Anga, thus elevating his status to that of a prince. This act cements Karna’s loyalty to Duryodhana and deepens the rivalry between Karna and Arjuna.

The House of Wax

Duryodhana, envious of the Pandavas and desiring the throne of Hastinapur for himself, hatches a deadly plot with his uncle, Shakuni (King of Ghandara), and minister, Purochana. The plan involves building a palace made of lac and other flammable materials at Varanavata, inviting the Pandavas to reside there, and then setting it ablaze to kill them.

Purochana, a loyal servant of Duryodhana, oversees the construction of this dangerous palace, known as the Lakshagriha (House of Wax). The palace is crafted to appear luxurious but is designed to be a death trap, with its highly inflammable materials cleverly concealed.

The Pandavas, along with their mother Kunti, unsuspectingly move to the palace at Varanavata. However, they are warned about the plot by Vidura, a loyal uncle who uses cryptic language to alert Yudhishthira. Vidura secretly arranges for a tunnel to be built as an escape route from the house.

The night of the planned arson, the Pandavas hold a feast, inviting a large number of local women and children to ensure that Purochana, who was to light the fire, would delay his actions to avoid unnecessary slaughter. Later that night, after the guests leave, Bhima, the strongest of the brothers, drugs Purochana, ensuring that he remains asleep. The Pandavas and Kunti then escape through the tunnel, leaving the palace to burn with Purochana inside.

Draupadi

Draupadi was known for her beauty and intelligence. Born from a sacred fire, her father, King Drupada of Panchala, performed a great sacrifice to obtain a powerful ally against the Kuru dynasty and a daughter.

A swayamvara, a ceremony where a princess chooses her husband from among various suitors, was arranged for her. The challenge set for the suitors was an extremely difficult one: to string a mighty bow and shoot an arrow through a rotating fish’s eye, looking only at its reflection in a pool of oil.

Many princes and kings, including the Kauravas, attended the swayamvara, but none could accomplish the task. The Pandavas, still in disguise following their presumed death at the house of wax, were also present. Arjuna, disguised as a Brahmin, stepped forward to take the challenge.

To the astonishment of all present, Arjuna successfully strung the bow and shot the arrow through the fish’s eye, winning Draupadi’s hand. This led to a stir among the attendees, as some questioned the propriety of a Brahmin winning the contest and marrying a Kshatriya princess.

The Marriage with Five Brothers

After Arjuna won Draupadi at the swayamvara, the Pandavas returned to their mother, Kunti. Unaware of what they had brought back, Kunti, without seeing Draupadi, instructed them to share whatever they had won. This statement, made inadvertently, led to a complex situation where the Pandavas, honoring their mother’s words, agreed to marry Draupadi together, with each brother taking her as his wife in turn.

This decision was met with controversy but was eventually justified and accepted through various interpretations of dharma, including a past-life boon granted to Draupadi that she would have five husbands. Moreover, Sage Vyasa and Krishna supported this unique arrangement, citing dharma and destiny.

The marriage of the Pandavas to Draupadi not only strengthened their bond as brothers but also created a powerful alliance with the kingdom of Panchala.

The Division of Hastinapur

After surviving the assassination attempt in the House of Wax, the Pandavas return to Hastinapur. Their survival and return cause a moral dilemma for Dhritarashtra, the Kuru king. Balancing the righteousness of their claim to the throne and his affection for his own sons, the Kauravas, Dhritarashtra decides to divide the kingdom to avoid conflict.

The Pandavas are given Khandavaprastha, a barren, unprosperous land. However, with the help of Lord Krishna, they transform this land into a magnificent city, which they name Indraprastha

Yudhishthira, the eldest Pandava, aspires to become a world emperor and decides to perform the Rajasuya Yajna, an elaborate and prestigious sacrifice that symbolizes the supremacy of a king over other rulers. The preparation for the yajna involves inviting all significant kings and chieftains and obtaining their assent, either through diplomatic relations or, in some cases, conquest.

The Rajasuya Yajna is a grand event, attended by numerous kings, sages, and dignitaries, including Lord Krishna, Bhishma, Drona, and even the Kauravas. During the yajna, there is a moment of contention when it comes to deciding who should be honored first, but Lord Krishna is ultimately chosen, signifying his preeminence.

The Game of Dice

After the grandeur of the Rajasuya Yajna and the rising prominence of the Pandavas, Duryodhana’s envy reaches a boiling point. He conspires with his uncle Shakuni, a master at dice, to invite the Pandavas to a game of dice, knowing it to be Yudhishthira’s weakness. Shakuni is notorious for his cunning and his dice that never lose.

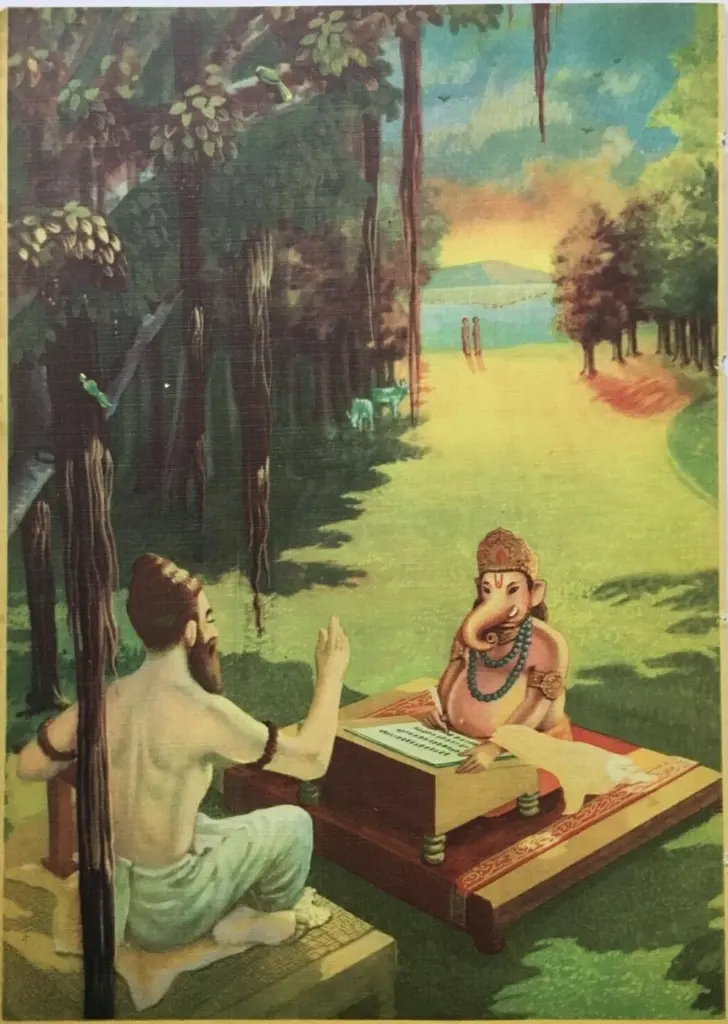

Yudhishthira, bound by the Kshatriya (warrior) code to never decline a challenge, accepts the invitation despite warnings from his brothers and well-wishers. The game is held in Hastinapur’s court, with both the Kauravas and Pandavas present. Shakuni plays on behalf of Duryodhana, while Yudhishthira gambles away his kingdom, wealth, his brothers, himself, and finally Draupadi, losing each time to Shakuni’s deceitful play.

Draupadi’s loss in the game of dice marks one of the most critical moments in the Mahabharata. Called into the court after being staked and lost in the game, she challenges the assembly on the legality of her being wagered in the first place. However, she is humiliated by Duryodhana and his brother Dushasana, who attempts to disrobe her in the full assembly.

It is at this moment of extreme distress that Draupadi’s honor is saved by divine intervention through Krishna, as her sari becomes endless, preventing her from being disrobed. This incident deeply wounds the Pandavas’ pride and sows the seeds of revenge in their hearts. Draupadi, in her humiliation, vows not to tie her hair until she has washed it with the blood of Dushasana. While Bhima made an oath to break Durodhana’s thighs and drink the blood of his brother Dushasana.

Seeing the situation escalating, Dhritarashtra, in an attempt to placate the situation, grants Draupadi a boon. She asks for the freedom of her husbands, and their wealth is returned. However, Duryodhana, unsatisfied and goaded by Shakuni, insists on another round of dice, proposing a final game with a condition: the loser would go into exile for 12 years, followed by a year of incognito living. If discovered during the thirteenth year, they would repeat the cycle.

Yudhishthira, once again, is drawn into the game and loses. As per the terms, the Pandavas along with Draupadi, leave for the forest, beginning their period of exile.

Life in the Forest

The early years of the Pandavas in exile were marked by a dramatic shift from palace life to the austerity of the forest. They settled in the woods, living a life of simplicity and penance. The forest life, while harsh, brought the Pandavas closer to nature and helped them understand the finer aspects of life and duty.

During their time in the forest, the Pandavas encountered numerous sages and saints. These encounters were opportunities for them to gain spiritual insights and learn about the broader aspects of dharma.

The Pandavas, especially Yudhishthira, engaged in deep discussions about duty with the sages they met. These dialogues often delved into the complexities of righteousness, the nature of justice, and the duties of a king and a warrior. Yudhishthira, known for his adherence to dharma, often found himself grappling with difficult ethical and moral questions, seeking to understand the right path.

Arjuna's Quest

Recognizing the inevitability of the impending war, Arjuna, embarked on a quest to acquire divine weapons that would be crucial in the battle against the Kauravas. He journeyed to the Himalayas, where he engaged in severe penance to please Lord Shiva. His austerities were so intense that they alarmed the gods, who decided to test his resolve.

Lord Shiva, disguised as a hunter, confronted Arjuna. In the ensuing battle between them, Arjuna’s exceptional skills and devotion impressed Shiva, who revealed his true form and blessed Arjuna. He granted Arjuna the Pashupatastra, a powerful weapon that could potentially destroy the world if not used judiciously.

Arjuna’s penance and subsequent favor from the gods did not end with Lord Shiva. He continued his quest, seeking out other deities and sages to obtain more divine weapons. Each god granted Arjuna unique weapons along with the knowledge of how to use them effectively and responsibly.

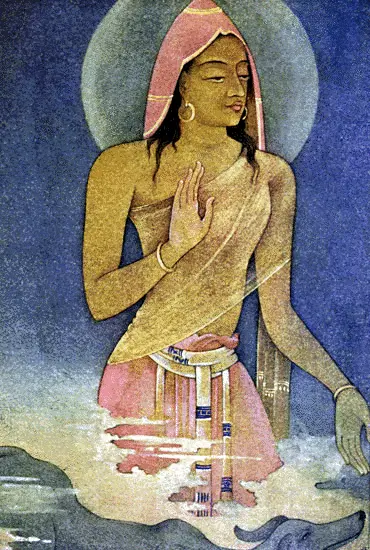

Arjuna’s quest eventually led him to the abode of his father, Indra, the king of the gods. In Indra’s heaven, Arjuna was trained in divine arts of music and dance, and he also received further training in warfare and advanced weaponry.

During his stay in Indra’s heaven, Arjuna had an encounter with the celestial nymph Urvashi. Urvashi, enamored by Arjuna’s prowess, expressed her desire for him. However, Arjuna respectfully declined her advances, citing his regard for her as equivalent to a mother figure, as she had once been a consort of his ancestor Pururava.

Offended by this rejection, Urvashi cursed Arjuna to become a eunuch. When Arjuna relayed this incident to Indra, his father modified the curse, limiting its duration to just one year – exactly the year of the Pandavas’ incognito stay. This curse, while initially seeming like a misfortune, turned out to be a boon as it helped Arjuna choose his disguise during the incognito period.

The Year in Disguise

As part of the exile terms agreed upon after the game of dice, the Pandavas were required to spend the final year in disguise, such that their identities remained hidden. If recognized, they would be obliged to repeat another 12 years of exile. Understanding the gravity of this condition, the Pandavas carefully devised a plan for their year in incognito.

They decided to split and hide in different places where they could remain undetected, yet be in positions where they could gather information and remain safe. The plan also involved choosing disguises that would effectively mask their true identities, taking into account their individual skills and personalities.

The Pandavas, along with Draupadi, chose the kingdom of Matsya, ruled by King Virata, for their incognito stay. The kingdom was chosen for its relative neutrality and the low likelihood of the Kauravas suspecting them to be there.

Each Pandava adopted a disguise that masked their true prowess and identity:

- Yudhishthira disguised himself as Kanka, a Brahmin, and served as an advisor in King Virata’s court.

- Bhima became Ballava, a cook and wrestler, utilizing his immense strength in a manner befitting his disguise.

- Arjuna, under the name Brihannala, took the guise of a eunuch and taught dance and music to the princess Uttara, using the curse of Urvashi to his advantage.

- Nakula assumed the identity of Granthika, a horse caretaker, leveraging his knowledge of horse-keeping.

- Sahadeva became Tantipala, a cowherd, applying his expertise in cattle rearing.

- Draupadi disguised herself as Sairandhri, a maid, serving Queen Sudeshna, the wife of King Virata.

During their stay at King Virata’s court, the Pandavas managed to keep their true identities hidden, despite several challenges and close calls.

Draupadi, as Sairandhri, faced a difficult time, especially when Queen Sudeshna’s brother, Kichaka, developed a lustful eye for her, leading to further complications and a subsequent incident where Bhima had to intervene, killing Kichaka in the process.

Brothers of the Wind

During their exile in the forest, Bhima had a significant encounter with Hanuman, his celestial brother, as they were both sons of the Wind God, Vayu.

This meeting occurred when Bhima was searching for a fragrant and powerful flower (Saughandhika) for Draupadi. He ventured deep into the forest and came across an old monkey whose tail was blocking his path. Bhima, unaware of the monkey’s true identity, arrogantly asked it to move its tail. However, when he tried to move the tail himself, he couldn’t, despite his immense strength.

Realizing he was in the presence of someone extraordinary, Bhima humbled himself, and Hanuman revealed his true form. They shared a moment of brotherly affection, and Hanuman imparted lessons of humility, strength, and devotion. Hanuman also promised Bhima that he would be present on the Pandava’s flag during the battle of Kurukshetra, symbolically indicating his support.

The End of the Exile

The incognito period of the Pandavas in the kingdom of Matsya came to a dramatic end with the conclusion of the one-year term. This period was marked by a significant event in the court of King Virata, which eventually led to the Pandavas revealing their true identities. The event unfolded when the kingdom was attacked by the neighboring kingdom of Trigarta, and simultaneously, the Kauravas attempted to steal the cattle of King Virata.

Arjuna, who had been living as the eunuch Brihannala, played a role in defending the kingdom. He retrieved his hidden weapons and, along with his brothers, repelled both the Trigarta and Kaurava armies.

The Pandavas’ successful defense of Matsya’s kingdom led to the revelation of their true identities. King Virata, upon realizing that the individuals who had been serving in his court were none other than the Pandavas, was both shocked and honored. He offered his daughter, Uttara, in marriage to Arjuna’s son Abhimanyu, thus forming an alliance with the Pandavas.

This revelation also marked the successful completion of the terms of their exile. The Pandavas, having adhered to the conditions of living incognito without being discovered, were now ready to rightfully reclaim their kingdom.

Following their return from exile, the Pandavas, led by Yudhishthira, sought to reclaim their kingdom through diplomatic means before resorting to war. They sent envoys to Hastinapur to negotiate the return of their kingdom, as was agreed upon before the exile; but it was all for naught.

Preparations for War

With the failure of diplomatic efforts and the inevitability of war becoming apparent, both the Pandavas and Kauravas began extensive preparations. This phase involved forming alliances with various kingdoms and assembling armies for the impending conflict.

The Pandavas, leveraging their relationships and righteousness of their cause, secured alliances with powerful kings like Drupada of Panchala, Virata of Matsya, and many others.

On the other hand, the Kauravas, led by Duryodhana, also amassed a formidable coalition, including alliances with kingdoms like Hastinapur, Gandhara (through Shakuni), and many others. Both sides gathered warriors, chariots, elephants, and vast infantries, preparing for a war on a scale never seen before in the history of Bharatvarsha.

Sri Krishna

A pivotal moment in the preparations for war was the solicitation of support from Krishna. Both Arjuna and Duryodhana went to seek Krishna’s assistance in the war. They found Krishna asleep and waited for him to awaken. Arjuna, humbler, stood at the feet of the sleeping Krishna, while Duryodhana, displaying his typical pride, sat by Krishna’s head.

When Krishna woke up, he saw Arjuna first since he was at his feet. Though Duryodhana claimed he arrived first and therefore deserved first choice in seeking aid, Krishna offered them a choice: one could choose his entire army, the Narayani Sena, and the other could choose Krishna himself, who vowed not to wield weapons in the war. Arjuna, without hesitation, chose Krishna, valuing his counsel and presence over the mighty army. Duryodhana was pleased to take the formidable army, believing it to be the superior choice.

Before the outbreak of war, there were last-ditch efforts to negotiate peace. Krishna himself went to Hastinapur as an emissary of peace, proposing that the Pandavas would be content with just five villages, avoiding the need for war. However, Duryodhana, blinded by arrogance and hate, refused to cede even a needlepoint of land to the Pandavas.

The Calm Before the Storm

The stage for the epic battle was set at Kurukshetra, a vast plain known for its sacredness. As the two factions assembled, the scale of the impending war became evident. On one side were the Pandavas, supported by allies they had garnered through their years in exile and their reputation for righteousness. Their forces were arrayed in strategic formations, led by great warriors like Drupada, Virata, and their own brothers.

On the other side, the Kauravas amassed a vast and formidable army, with warriors from across the land, including legendary figures like Bhishma, Drona, Karna, and others. The Kauravas’ army was larger in number, and their formations mirrored the strength and skill of their leaders.

With peace negotiations failing, the focus shifted to preparing for the inevitable battle. The Pandavas and Kauravas made intricate plans, strategizing their formations and roles of various commanders. Bhishma was appointed as the commander-in-chief of the Kaurava army, while Dhrishtadyumna, the son of Drupada and brother of Draupadi, was chosen to lead the Pandava forces.

The night before the battle, both camps were scenes of solemn preparation, prayer, and reflection. Warriors sought blessings from their elders and deities, readying themselves for what was to come. The air was thick with anticipation, anxiety, and the weight of impending fate.

The Song of God

The Pandavas, particularly Arjuna, faced inner turmoil over the prospect of fighting their own kin, teachers, and revered elders. The Kaurava camp, though outwardly confident, was also fraught with its own moral quandaries, with warriors like Bhishma and Drona fighting for a cause they personally did not fully endorse but were bound to by loyalty and duty.

They pondered the righteousness of the war, the meaning of duty, and the impermanence of life and glory. These reflections brought to the fore the profound themes of dharma, karma, and the eternal cycle of life and death.

The most profound event on the eve of the war was the counsel given by Lord Krishna to a despondent Arjuna, who was torn about fighting his relatives. This dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra forms the essence of the Bhagavad Gita, a sacred Hindu scripture.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna imparts spiritual wisdom and guidance to Arjuna, addressing his doubts and confusion. He speaks of various philosophical concepts such as the nature of the self, the importance of duty, and the paths to spiritual liberation. Krishna urges Arjuna to fulfill his Kshatriya duty to fight, emphasizing that the soul is immortal and that he is only fighting the body. He introduces the concept of “Nishkama Karma” – the idea of performing one’s duty without attachment to the results.

Arjuna, enlightened by Krishna’s teachings, resolves his inner conflict and decides to fight, recognizing that it is his duty to uphold righteousness and justice. His decision symbolizes the struggle and eventual reconciliation of moral and spiritual duty, which is central to the Mahabharata.

The Kurukshetra War

The great battle of Kurukshetra marked the culmination of the longstanding feud between the Pandavas and the Kauravas. It began with the blowing of conch shells, signaling the start of a war that would last for eighteen days and change the course of history. The initial battles were fierce, showcasing the might and valor of the greatest warriors from both sides.

From the outset, the war was characterized by intense combat, with both armies employing various formations (vyuhas) and strategies. The Pandavas, under the leadership of Yudhishthira and the strategic guidance of Krishna, fought with a focus on righteousness and justice. The Kauravas, led by Duryodhana and commanded by warriors like Bhishma, countered with equal ferocity and skill.

Both sides employed a wide array of strategies and tactics, ranging from conventional warfare methods to the use of celestial weapons (divyastras). The Pandavas, with their smaller army, often resorted to innovative tactics and formations to counter the might of the larger Kaurava force.

Bhishma, the commander of the Kaurava army for the initial days, proved to be a formidable opponent, causing significant casualties to the Pandava army. His strategy was to demoralize the Pandavas and seek a decisive victory.

The Fall of Bhishma

Realizing that the war could not be won as long as Bhishma was active, the Pandavas, particularly Arjuna, were in a moral dilemma. Bhishma, being their elder and a revered figure, was not someone they wanted to harm. However, on Krishna’s counsel, they devised a strategy to bring him down. Bhishma himself, aware of the quandary faced by Arjuna, hinted at the means of his downfall.

The turning point came when Arjuna placed Shikhandi, who was actually Amba in a previous life, in his chariot in front of him. Bhishma, recognizing Shikhandi, refused to fight against her, allowing Arjuna to target him effectively. Showered by a volley of arrows from Arjuna, Bhishma fell, but due to the boon of choosing the time of his death, he remained on a bed of arrows, alive, awaiting the auspicious moment to leave his body.

The great warrior, lying on the bed of arrows, became a source of wisdom in his final days. During this time, he was visited by many, including the Pandavas.

In these moments, Bhishma imparted valuable teachings on various subjects, including dharma, statecraft, the duties of a king, and the principles of governance. These discourses, known as the Shanti Parva in the Mahabharata, are a treasure trove of wisdom and provide deep insights into ancient Hindu philosophy.

Abhimanyu

Abhimanyu, the son of Arjuna and Subhadra (Krishna’s sister), was a formidable warrior despite his young age.

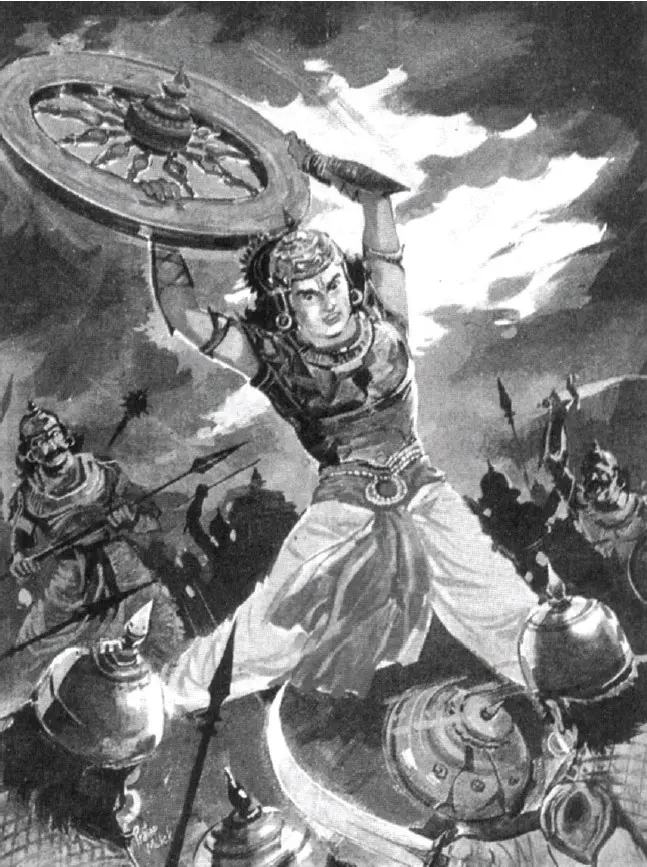

On the fateful day when the Kauravas deployed the Chakravyuha formation, a complex and almost impregnable battle tactic, the Pandavas faced a significant challenge. Abhimanyu was one of the few warriors on the Pandava side who knew how to penetrate this formation. He bravely stepped up to take on this daunting task.

As Abhimanyu began his assault and entered the Chakravyuha, his valor and skill were evident. The Pandavas planned to follow him to provide support and ensure his safe exit, which he was not aware of. However, the Kauravas, anticipating this move, strategically intercepted and engaged the other Pandavas in different parts of the battlefield, effectively preventing them from accompanying Abhimanyu. This left him isolated inside the enemy formation.

Trapped inside the Chakravyuha, Abhimanyu displayed extraordinary fighting skills, holding his own against the Kaurava warriors. As the battle intensified, he found himself surrounded by some of the most seasoned Kaurava warriors, including Drona, Karna, Duryodhana, Dushasana, Ashwatthama (Drona’s son) and others. These veteran warriors collectively attacked Abhimanyu, a breach of the ethical conduct of battle which dictated fair single combat.

In a remarkable display of bravery and ingenuity, Abhimanyu continued to fight fiercely even after his chariot was destroyed. He took up a chariot wheel and used it as a weapon! Despite his valiant efforts, the numerical superiority and combined might of the Kaurava warriors eventually overwhelmed him.

The death of Abhimanyu was a major turning point in the war. Not only did it showcase the prowess and heroism of the young warrior, but it also highlighted the increasingly desperate and unethical tactics employed as the war progressed. The manner of his death, at the hands of multiple veteran warriors, was seen as a dishonorable act, deeply affecting the Pandavas, especially Arjuna, who vowed to avenge his son’s death.

The Deception of Drona

After Bhishma’s fall, Drona, the revered guru of both the Pandavas and the Kauravas, took over as the commander of the Kaurava forces. Drona, a master in archery and warfare, led the Kauravas with great skill and might. Under his command, the war saw some of the most intense and strategic battles. Drona’s main objective was to capture Yudhishthira alive, as per Duryodhana’s plan to end the war by demoralizing the Pandavas.

As the war progressed, it became increasingly clear to the Pandavas that Drona’s expertise and leadership were too formidable. Krishna, understanding that Drona could only be subdued through unconventional means, suggested a plan involving deception.

The Pandavas resorted to a ruse to bring about Drona’s downfall. They spread the false news of his son Ashwatthama’s death, knowing that Drona, deeply attached to his son, would be devastated and lose the will to fight. To convince Drona of the lie, Bhima killed an elephant named Ashwatthama and loudly proclaimed that Ashwatthama was dead. Drona, in disbelief, approached Yudhishthira, known for his truthfulness, to confirm the news. Yudhishthira ambiguously declared “Ashwatthama is dead, but it is not the man, it is the elephant,” with the latter part of his statement being drowned out by the sound of conch shells.

Believing his son to be dead and heartbroken, Drona laid down his weapons, and in that moment of vulnerability, he was killed by Dhrishtadyumna.

Vows Fulfilled

As the war progressed, the opportunity for Bhima to fulfill this vow presented itself. In a ferocious battle, amidst the chaos and violence of the war, Bhima faced Dushasana. Fueled by years of anger and the burning desire for retribution, Bhima engaged in a deadly combat with Dushasana, eventually overpowering and killing him.

In a dramatic and gruesome display of vengeance, Bhima tore open Dushasana’s chest, took his blood, and, as per his vow, drank it. This act was not just a fulfillment of his promise but also a symbol of the Pandavas’ retribution for the atrocities they had suffered.

Following the killing of Dushasana, Draupadi, in a powerful symbolic act, washed her hair with his blood. This act signified the fulfillment of her own vow and represented a moment of closure and justice for the humiliation she had endured. It was a significant moment for Draupadi, marking the end of a long-held grievance and the upholding of not only her dignity, but for all women.

The Death of Karna

With Drona out of the picture, the mantle was then passed on to Karna.

A warrior of unparalleled skill and a true friend to Duryodhana, Karna was the secret eldest son of Kunti and the Sun God, making him the Pandavas’ half-brother, a fact unknown to him and the Pandavas until his final moments.

In the decisive duel with Arjuna, Karna’s chariot wheel got stuck in the mud. While trying to free it, he remembered the curse of the sage Parashurama – that he would be helpless in a critical moment of battle. As Karna stood defenseless, Arjuna, urged by Krishna, delivered the fatal arrow, killing Karna.

Duryodhana

Following Karna’s death, the Kaurava forces were severely weakened. Duryodhana, distraught and demoralized by the deaths of his brothers and key allies, chose to engage in a final battle with Bhima.

As per their long-standing vow, the two engaged in a fierce mace fight, which ended with Bhima dealing a fatal blow to Duryodhana’s thighs, a move that was against the rules of combat. This act symbolized both the fulfillment of Bhima’s vow and the moral decline that had permeated the war.

With Duryodhana’s defeat, the Kaurava resistance crumbled, and the Pandavas emerged victorious. However, their victory was bittersweet, marred by the immense loss of life and the moral complexities that arose during the war.

Aftermath

After the conclusion of the Kurukshetra War, the Pandavas, despite emerging victorious, were engulfed in a profound sense of grief and loss. The battlefield was strewn with the bodies of countless warriors, including many of their own relatives, friends, and revered teachers. The sheer scale of death and destruction led to deep introspection about the war’s worth and its moral implications.

Yudhishthira, in particular, was haunted by the cost at which victory had come. He grappled with guilt and moral questions, troubled by the deaths he felt responsible for.

After much deliberation and counsel from sages, Krishna, and his surviving family members, Yudhishthira agreed to ascend the throne of Hastinapur. His coronation marked the beginning of a new era, one that sought to heal the wounds of the past and rebuild the kingdom from the ravages of war.

He then performed the Ashwamedha Yajna at the behest of Krishna, a horse sacrifice ritual symbolizing the establishment of his authority over the land.

Yudhishthira’s rule was characterized by justice, wisdom, and compassion. Known for his adherence to righteousness, he strived to be a fair and benevolent ruler, focusing on the welfare of his subjects and the restoration of peace and prosperity in the kingdom. His reign symbolized a return to stability and ethical governance after a period of intense conflict and moral decline.

The Pandavas' Final Journey

After ruling Hastinapur for many years and establishing a reign of peace and prosperity, Yudhishthira decided it was time to leave the material world behind. He passed the kingdom to Parikshit, Arjuna’s grandson, and along with his brothers and Draupadi, embarked on a final journey, renouncing all worldly ties and possessions. This journey, known as the Mahaprasthanika Parva, was a pursuit of spiritual liberation and the culmination of their earthly duties.

As they trekked towards the Himalayas, a dog joined and followed them. Along the way, one by one, Draupadi and the brothers, except Yudhishthira, fell to their deaths. Their falls were attributed to their respective shortcomings, which were symbolically tied to their earthly attachments. For example, Draupadi’s partiality towards Arjuna, and each brother’s personal vice such as pride and gluttony.

Yudhishthira, who did not falter, continued his journey with the dog by his side.

The Dog

Upon reaching the summit, Yudhishthira was greeted by the god Indra, who arrived in his celestial chariot to take him to heaven. However, when Indra asked Yudhishthira to abandon the dog before entering the chariot, Yudhishthira refused. Despite Indra’s insistence that the dog could not accompany him to heaven, Yudhishthira stood firm in his decision.

Yudhishthira’s refusal was rooted in his unwavering commitment to dharma. He argued that abandoning a loyal and devoted creature, one that had accompanied him through the hardships of the journey, was an act of cruelty and unrighteousness. He expressed that such an act would taint all his meritorious deeds and virtues.

Moved by Yudhishthira’s steadfast morality, the dog then revealed its true form. It was none other than Dharma, the god of righteousness, who had taken the form of a dog to test Yudhishthira’s virtue in his final moments.

Yudhishthira

After passing this final test, Yudhishthira was allowed to ascend to heaven in his mortal body, a rare honor bestowed upon him for his unflinching adherence to dharma.

Before ascending to heaven, Yudhishthira was taken to hell, where he saw his brothers and Draupadi suffering. Disturbed by this sight, he insisted on staying in hell with them if that was the price of their actions. This was the final test of his virtue. It turned out to be an illusion, a test of his loyalty and commitment to his family and principles.

Yudhishthira then ascended to heaven, where he found his brothers, Draupadi, and even Duryodhana, all restored to their divine forms. This concluded the Pandavas’ earthly journey, symbolizing the triumph of dharma and the importance of righteousness and moral integrity.

The final journey of the Pandavas encapsulates the essence of the Mahabharata’s teachings on dharma, the impermanence of life, and the ultimate spiritual journey of the soul.

Why is the Mahabharata Important?

The Mahabharata’s significance lies in its intricate portrayal of human nature and society, showcasing the complexities of emotions, relationships, ambitions, and conflicts. It

serves as a profound ethical and philosophical guide, exploring themes such as duty, righteousness, and the nature of the self, particularly through dialogues in the Bhagavad Gita.

As a moral compass, the epic prompts us to reflect on our own ethical choices, navigating through the gray areas of morality and righteousness.

Additionally, the Mahabharata stands as a cultural encyclopedia of ancient India, offering insights into various aspects like politics, law, warfare, and social customs. This wealth of information makes it an invaluable resource for understanding historical and cultural contexts.

The epic’s influence pervades various art forms, illustrating universal truths and human dilemmas that transcend time and geography.

Its stories and characters encourage introspection about personal and societal struggles, making the Mahabharata not just a cornerstone of Indian heritage but a timeless piece of literature offering wisdom to successive generations globally.

Life Lessons from the Mahabharata

Say No to Gambling: Perhaps one of the most direct and practical life lessons is the perils of gambling. The epic highlights the importance of self-control, the dangers of addiction, and the severe repercussions that impulsive and reckless decisions can have on one’s life and the lives of those around them.

Complexity of Dharma: The Mahabharata teaches that dharma is not always black and white. It shows how dharma can be complex and contextual, urging individuals to consider the larger good and ethical implications of their actions.

Consequences of Actions: The epic underscores the principle of karma, emphasizing that every action has consequences. It encourages mindfulness and responsibility in actions, as they shape not only the individual’s destiny but also the lives of others around them.

Importance of Counsel: The value of wise counsel and the need for guidance in difficult times are recurring themes. The characters who seek and heed wise counsel, like Arjuna turning to Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, often find the right path.

Impermanence of Power and Wealth: The transient nature of power, wealth, and worldly success is highlighted throughout the epic. It teaches that true greatness lies not in material possessions but in righteousness and moral integrity.

Significance of Inner Transformation: The Mahabharata illustrates that real victory is the triumph over one’s lower self. It emphasizes the importance of self-reflection and inner transformation in achieving true success and fulfillment.