The Great Flood, a cataclysmic event said to have submerged vast regions of the Earth, is more than a mere historical phenomenon.

It is a tale woven into numerous cultures, a shared narrative that transcends geographical boundaries and reaches into the core of human existence.

From the ancient Mesopotamians to Native American tribes, the theme of a great flood resonates across the world.

It’s found in the religious texts of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, in the epic poetry of ancient Greece, and in the oral traditions of far-flung indigenous peoples.

But why?

This universal motif speaks to something profound about the human experience, possibly reflecting shared memories or perhaps deep-seated fears.

And it does make one wonder: Is the Great Flood a mere allegory, or does it have a basis in historical fact?

Read on as we dive deep into the stormy stories of the Great Flood!

Table of Contents

Toggle

What is the Great Flood?

The Great Flood is not a single story but a mosaic of myths that permeate the folklore of various cultures, depicting a catastrophic deluge that engulfs the world.

These myths often begin with a warning to chosen individuals about an impending flood.

This warning sets in motion a series of events where the chosen ones prepare for the deluge, either by building a vessel or finding refuge.

These myths invariably lead to a flood of unimaginable proportions that destroys almost everything in its path.

Following the huge deluge, the few survivors begin the arduous process of rebuilding and repopulating the world.

The Great Flood Across Cultures

Mesopotamian Mythology

The Mesopotamian region, known as the cradle of civilization, offers some of the earliest recorded flood myths:

- Sumerian Flood Story

The Sumerian Flood Story, documented in the “Eridu Genesis,” is one of the oldest known accounts of the Great Flood. Dated to around the 17th century BCE, this text describes the gods’ decision to destroy mankind with a flood due to their displeasure with human misbehavior.In the story, the god Enki takes pity on a pious king named Ziusudra, warning him of the coming catastrophe.

Following Enki’s guidance, Ziusudra constructs a large boat and gathers inside it his family and a collection of animals and plants. After the waters recede, Ziusudra offers sacrifices to the gods and is granted immortality as a reward. - Epic of Gilgamesh

Possibly the most famous of the Mesopotamian flood narratives, the “Epic of Gilgamesh,” written in Akkadian, chronicles the adventures of Gilgamesh, a historical king of Uruk. Within this broader epic, the flood story appears as a significant episode. The tale is related to Gilgamesh by Utnapishtim, a character with striking parallels to the Sumerian Ziusudra.

Utnapishtim recounts how he was warned by the god Ea about the other gods’ intention to flood the world. Following the divine instructions, Utnapishtim builds a massive ark, filling it with his family, skilled craftsmen, and “the seed of all living creatures.” After surviving the flood, Utnapishtim, like Ziusudra, offers sacrifices to the gods and is granted immortality.

Abrahamic Traditions

The story of Noah’s Ark and the Great Flood is one of the most recognized and revered narratives in the Abrahamic traditions. Though the details may vary slightly among Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the essential elements remain consistent:

- Judaism

In the Hebrew Bible, specifically in the Book of Genesis, God, displeased with human wickedness, decides to cleanse the Earth with a flood, sparing only the righteous Noah, his family, and a pair of each animal species. Noah’s obedience to God’s commands, his construction of the Ark, and the eventual subsiding of the floodwaters become emblematic of faith, divine justice, and renewal. - Christianity

Christian interpretations of the Noah story often align closely with the Jewish tradition but also emphasize the themes of salvation and baptism. The Apostle Peter, in the New Testament, draws a parallel between the saving waters of the flood and the sacrament of baptism, representing a purification from sin and a new beginning in Christ. - Islam

As one of the five major prophets in Islam, Nuh’s (Noah) story is recounted in several chapters of the Qur’an. In the Islamic account, Nuh preaches to his people for 950 years, urging them to abandon idolatry and worship the one true God. When his pleas are ignored, God commands Nuh to build the Ark and gather the believers and animals. The Qur’an emphasizes Nuh’s unwavering faith, portraying him as a model of steadfastness to God’s will.

Greek Mythology

According to Greek mythology, The gods, led by Zeus, become disillusioned with the moral decay and impiety of the Bronze Age humans.

Deciding that humanity must be purged to restore cosmic order, Zeus resolves to flood the Earth.

Deucalion, the son of Prometheus, is warned of the impending disaster by his father, who has the gift of foresight. Following Prometheus’s instructions, Deucalion builds an ark and boards it with his wife, Pyrrha.

The deluge that follows lasts for nine days and nights, submerging the land and wiping out nearly all of humanity.

Once the waters recede, Deucalion and Pyrrha find themselves on Mount Parnassus, bewildered and alone.

Guided by a cryptic oracle from the goddess Themis, they understand that they must “throw the bones of their mother” behind them.

Realizing that “mother” refers to Earth, they throw stones, which miraculously transform into new human beings – men from the stones thrown by Deucalion and women from those thrown by Pyrrha.

Hindu Mythology

Manu, a progenitor of humanity, encounters the fish avatar of Lord Vishnu, Matsya, who warns him of an impending deluge that will consume the world.

Recognizing the divine nature of the fish, Manu agrees to protect it from a larger predator fish. In gratitude, Matsya reveals to Manu the date of the coming flood and instructs him to build a massive ship.

Following Matsya’s guidance, Manu constructs the ship and gathers the sacred Vedas, medicinal herbs, and various species of seeds and animals. As the floodwaters begin to rise, Matsya guides the ship to the safety of a mountaintop, tethering it to the Himalayan peak using a cosmic serpent.

Once the waters recede, Manu alone repopulates the Earth, assisted by the divine guidance of the Creator god Brahma.

In this role, Manu embodies the archetypal first man, much like Adam in the Abrahamic tradition or Yima in Zoroastrianism.

Chinese Mythology

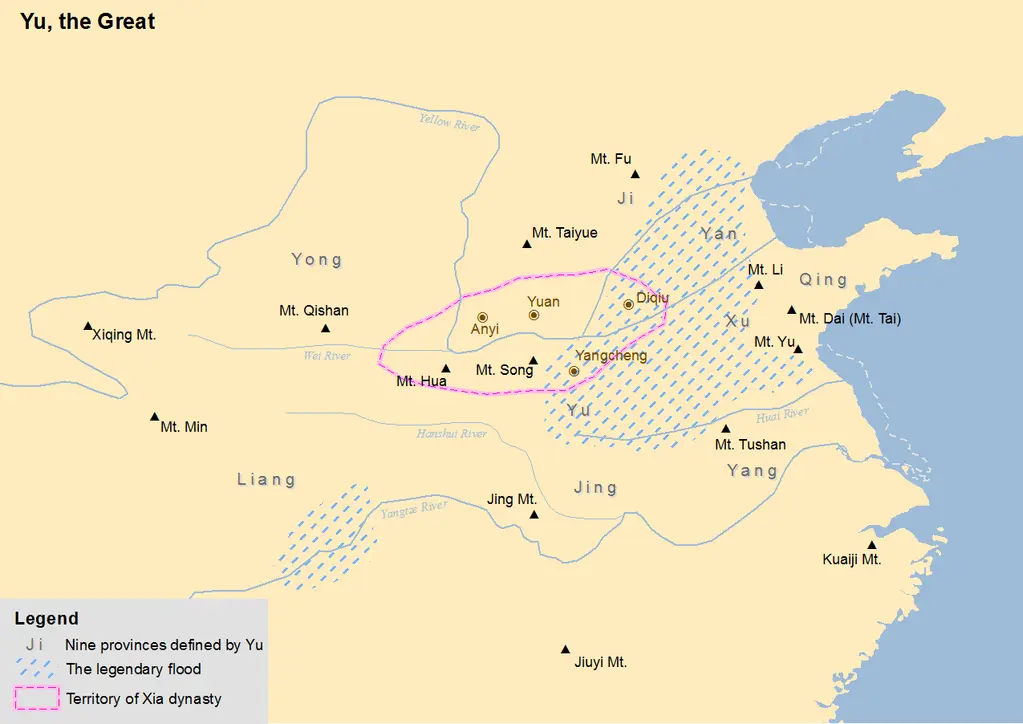

The Chinese Great Flood is dated by tradition to the third millennium BCE and is prominently featured in texts like the “Book of Documents” and “Classic of Mountains and Seas.” Unlike many other flood myths that focus on divine wrath and retribution, the Chinese account emphasizes human ingenuity, responsibility, and collaboration with the divine.

According to the legend, the flood began during the reign of Emperor Yao. The deluge was relentless, inundating the land for generations, causing widespread chaos and suffering.

Yao appointed Gun, a prince, to control the flood, but despite his efforts, which included building massive dikes and dams, the flood continued unabated.

After nine years of failure, Gun’s son Yu the Great took over the task. Instead of trying to contain the flood, Yu sought harmony with nature.

He organized a massive effort to dredge new river channels, allowing the floodwaters to flow back to the sea. This labor took thirteen years, during which Yu displayed immense dedication, even neglecting to visit his home.

Yu’s success in taming the flood marked the beginning of the Xia Dynasty and set the standard for virtuous leadership in Chinese culture.

The Chinese flood myth also integrates cosmological concepts, reflecting the importance of balance (Yin and Yang) and the interdependence of humanity and the natural world. The tale underlies principles such as Confucian ethics and Taoist philosophy.

Mesoamerican Traditions

Mesoamerican cultures have also contributed fascinating flood narratives:

- The Aztecs

In Aztec mythology, the world has gone through several ages, each ending in destruction. The fourth era, known as the Sun of Water, ended with a catastrophic flood. Only a man, Coxcoxtli, and a woman, Xochiquetzal, survived by floating in a hollow log. After the flood, they repopulated the world, giving rise to the fifth and current era. - The Mayans

The ancient Maya had a nuanced view of creation, featuring cycles of destruction and renewal. One of these cycles ended with a great flood sent by the Heart of Sky, a supreme deity, to cleanse the world of an imperfect version of humanity. The flood serves as a prelude to the creation of modern humans from maize dough. - The Incans

According to Incan tradition, the creator god Viracocha was displeased with the first race of giants he created, finding them unruly and defiant. In response, he sent a flood to wipe them out, a calamity known as Unu Pachakuti, or the “water overturning of the world.” Only a few giants survived, turned into stone, and one man and woman were saved in a wooden box. After the flood, Viracocha created a new and improved race of human beings, along with the sun, moon, and stars.

Native American Traditions

Native American cultures, with their diverse tribes and rich oral traditions, provide numerous interpretations of the Great Flood:

- Hopi Tribe

In the Hopi tribe’s account of the Great Flood, the people are living in a wicked manner, and the Spider Grandmother (the very same one in the Dream Catcher legend) warns them of a flood sent by the Creator, Sotuknang. The virtuous are saved by floating on reeds, while the sinful perish. After the flood, the survivors are instructed to respect all life and live in harmony with nature. - Choctaw Tribe

The Choctaw tribe tells of a prophet who warns the people about a flood due to their misbehavior. Those who listen are saved by fleeing to a sacred mound, Nanih Waiya. After the flood, the survivors offer thanks and promise to honor the Creator’s laws.

- Ojibwe Tribe

In the Ojibwe tradition, a great flood cleanses the Earth of wickedness. Nanabozho, a cultural hero, survives by floating on a log with various animals. Together, they create a new world by diving into the water to bring up mud.

Historical Evidence of the Great Flood

Geological studies have uncovered evidence of massive flood events in different parts of the world. For example, the Black Sea deluge hypothesis suggests that a catastrophic flooding event around 7,600 years ago may have inspired the Mesopotamian flood myths.

Similarly, glacial meltwater bursts and large-scale river floods have been found in various regions, providing potential geological bases for local flood narratives.

Meanwhile, archaeological discoveries have provided tangible links to some flood myths. Excavations in the Mesopotamian region have revealed layers of silt and clay in ancient settlements, indicating significant flooding events.

In China, the discovery of the remains of an ancient dam and irrigation system supports the historical authenticity of the story of Yu the Great.

Climate changes and natural disasters have played crucial roles in shaping human history, and their impact is reflected in flood myths. For instance, the end of the last Ice Age caused significant sea level rises and flooding in coastal regions.

Symbolism of the Great Flood

Psychology

Psychologists, particularly those influenced by Carl Jung’s theory of archetypes, have examined the Great Flood as a symbolic expression of the collective unconscious.

The flood motif may represent a universal fear of chaos and the unknown, a purging of sins, a yearning for renewal and transformation.

This psychological lens helps uncover the emotional resonance and enduring appeal of flood myths, reflecting shared human anxieties, desires, and existential concerns.

Morality

Flood myths often contain moral lessons that articulate the values, ethics, and social norms of a particular culture.

They typically depict a divine judgment on human misbehavior, greed, or arrogance, teaching lessons about humility, obedience, compassion, and harmony with nature.

The narratives function as allegorical warnings, guiding behavior, and reinforcing societal cohesion and moral order.

Creation

Many flood stories are closely intertwined with creation myths and cosmogonies, symbolizing both destruction and rebirth.

In some traditions, the flood serves as a transition between cosmic epochs or as a cleansing process paving the way for a new era.

These narratives reflect an understanding of cyclical time, where creation, sustenance, and dissolution are interconnected phases of existence. In Hinduism, this is further represented by Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva respectively.

The symbolism of water as both life-giving and destructive embodies this dual nature of creation.

Scientific Perspectives of the Great Flood

Glacial Melting

Scientific studies have linked significant historical floods to the melting of glaciers, particularly at the end of the last Ice Age. The release of vast quantities of meltwater into oceans and rivers caused substantial sea level rise, inundating coastal areas and transforming landscapes.

Tectonic Activity

Tectonic forces, including earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and the movement of tectonic plates, have contributed to sudden and catastrophic flood events.

Tsunamis generated by undersea earthquakes or volcanic eruptions have caused widespread devastation, possibly inspiring regional flood myths.

Meteorological Phenomena

The role of weather and climate in flood narratives is evident in descriptions of relentless rains, storms, and other meteorological phenomena.

Monsoons, hurricanes, and cyclones have been linked to historical flooding events, captured in myths that convey the awe, fear, and fascination with nature’s fury.

Implications of the Great Flood

The Great Flood, a narrative that transcends time and borders, resonates within the soul of humanity.

It’s not merely a story confined to the annals of mythology but it’s a living symbol that continues to ripple through the collective consciousness.

In every drop of this universal deluge lies the reflection of humanity’s deepest fears and greatest hopes.

It is the mirror of our imperfections, our struggles, and our relentless pursuit of redemption.

But perhaps the most mind-blowing revelation isn’t merely in understanding the Great Flood as a story but as a living prophecy.

It’s a reflection of our world today, a world grappling with ecological imbalance, ethical dilemmas, and existential uncertainty.

As we stand at the intersection of myth and reality, the Great Flood serves as a profound reminder that we are the authors of our destiny, the architects of our world.